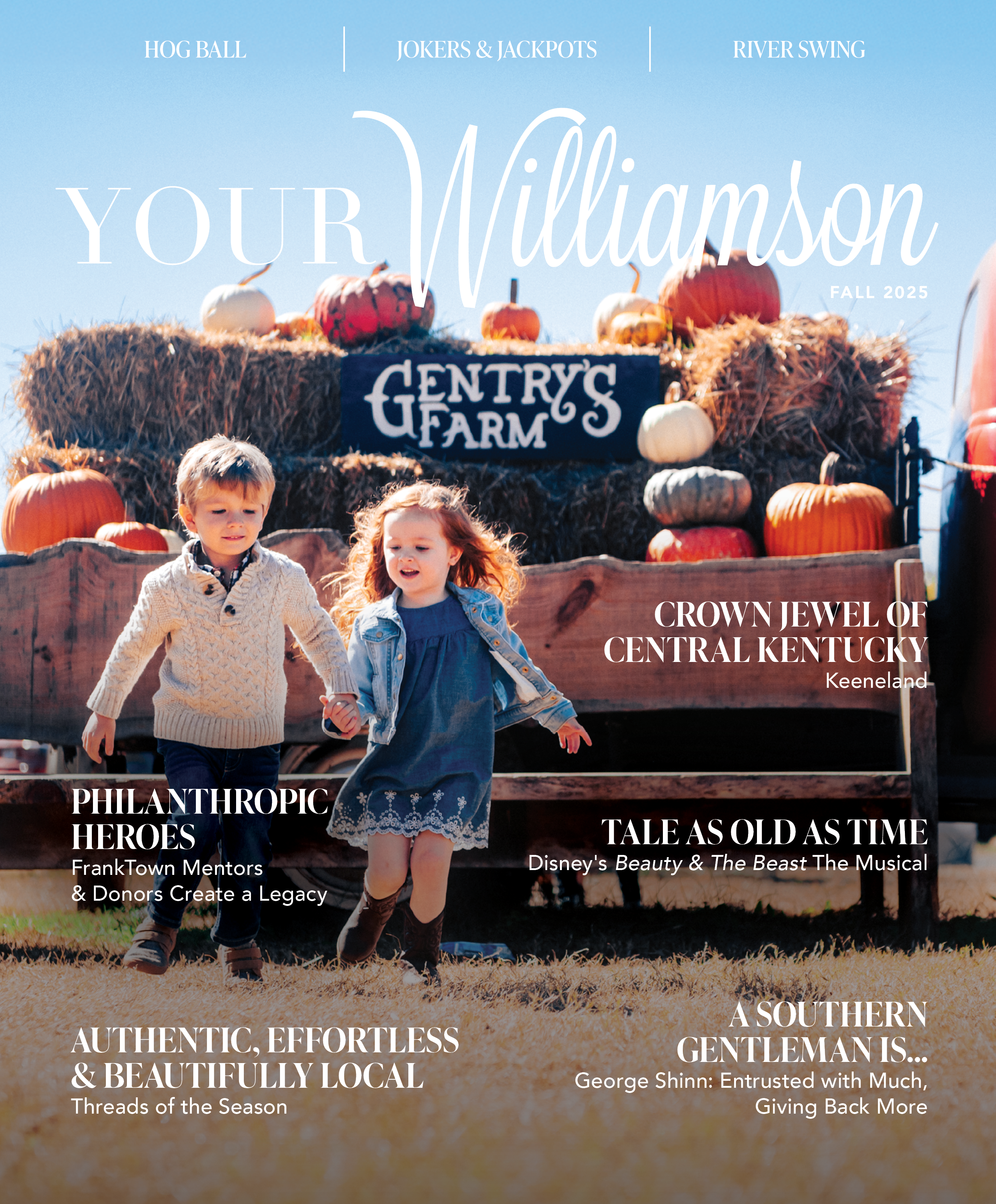

PUMPKINLAND – HOW ONE MAN CARVED OUT A NAME FOR HIMSELF IN FRANKLIN’S HISTORY

Nowadays in Williamson County, it isn’t fall without a trip to Gentry’s Farm, but several decades ago, the changing leaves and nip in the air meant it was time to visit Pumpkinland at Earl’s Fruit Stand.

Earl Tywater opened his produce market in 1957, first operating out of a plywood shed on Franklin’s East Main Street. He later moved across the street into a rambling, low-slung building that white-knuckled the banks of the Harpeth River. Interestingly, his father was a sharecropper who once farmed the same land where Earl set up shop.

For the bulk of the year, Earl’s Fruit Stand looked like most businesses of its variety. Empty crates and bushel baskets teetered in stacks against the storefront. Birdhouses and lawn ornaments dotted the property. In the spring and summer, flowers boiled over pots, trays and hanging containers, creating a scene so lush it felt Amazonian.

Inside, cured hams, seasoned gourds, and dried peppers dangled from the ceiling like unconventional party decorations. Bins of fruits, vegetables and seeds fought for space on the floor, all the while imbuing the air with an earthy scent.

But come autumn, Earl’s Fruit Stand underwent a transformation of mythic proportions. Seemingly overnight, the modest country market became Pumpkinland, a magical world of Halloween thrills, farm animals, and, you guessed it, pumpkins.

It all started one fall in the seventies when Earl’s wife, Ann, decorated their shop with carved pumpkins. Her display became an annual tradition, and with each passing year, the family flexed more of their creative muscles. Earl’s daughter, Tammy, painted pumpkins to look like celebrities and politicians. Earl built covered stalls along the river, trucked in animals from his nearby farm, and created a petting zoo. A haystack maze was added to the mix, as well as a Boo Barn and pony rides.

We are talking scale-tipping, county-fair-worthy, 700-pound gourds. No kidding, in the eighties, he even hollowed one out and stuck a pony inside. When asked where his giants came from, he would smile and simply say, “Up the river.”

It wasn’t long before Earl became known as the “Pumpkin King of Middle Tennessee.” Schools from all across the region began bussing children to Pumpkinland for field trips. Countless families made treks to Earl’s as part of their fall rituals. The modest fruit stand on the river turned into a destination, a tradition, and, eventually, a treasured memory.

After forty-three years of running his business, Earl died in 2000. The family kept the stand open a few more years, but ultimately made the difficult decision to sell. In 2010, the land was auctioned off, and Earl’s was replaced by a brick mixed-use building.

Pumpkinland may be no more, but traces of it can still be found if you look in the right places. It lives on through faded photographs and swapped stories and knowing smiles. It lives on through the kids, now adults, who once visited that magical place. It lives on as they drive by and point out the spot to their own children. “Let me tell you a story about Pumpkinland,” they say, “and a pumpkin king named Earl…”