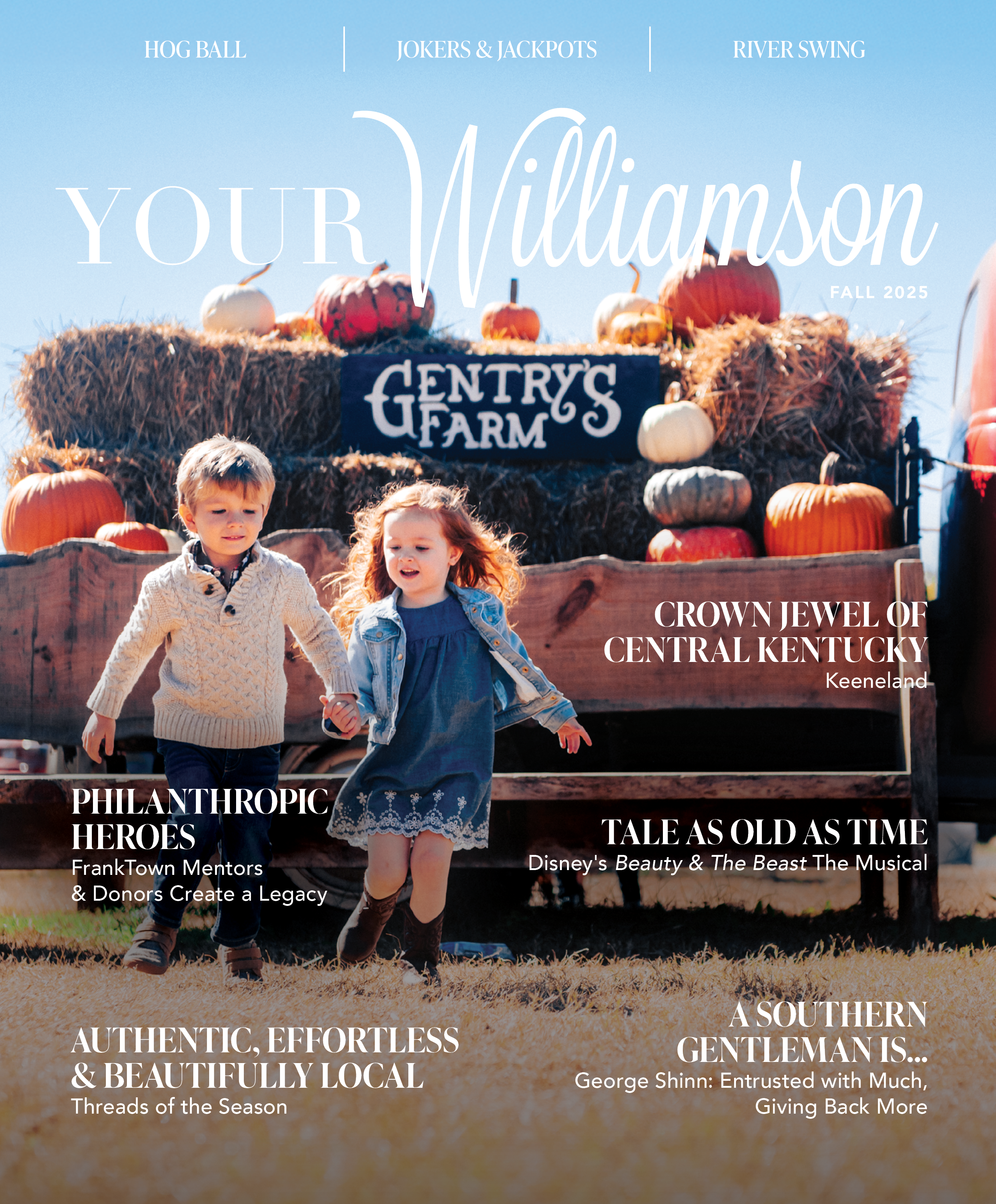

From a Fair Pavilion to a Storied Residence

BY Katie Shands

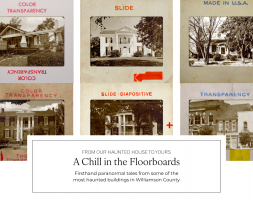

Perched on a hill overlooking New Highway 96 West, Centennial Hall looks as if it has always been there. However, the home is a Williamson County transplant, originally built in Nashville and later transported to its present site by horse-drawn wagons.

In its previous life, Centennial Hall was the Knights of Pythias Pavilion at the 1897 Tennessee Centennial Exposition. It served as a conference and resting space for the fraternity members and their families during the six-month celebration that marked Tennessee’s 100th anniversary of statehood. The building was one of more than 100 structures erected for the fair in what is now known as Centennial Park. The Knights of Pythias Pavilion stood near the Parthenon – torn down and rebuilt with permanent materials in the 1920s and early 1930s – and faced Lake Watauga. Designed by noted Nashville architect Henry Gibel, the dome-topped beauty was modeled in part after Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello.

Though all the fair’s structures were meant to be temporary, the future held a different path for the Knights of Pythias Pavilion. It would be the only original building from the exposition to ultimately survive. Soon after the fair, Joseph L. Parkes, Jr. purchased the pavilion with plans to move it to his Grand View Dairy Farm near Franklin and convert it into a residence. At the time, Joseph was courting Sophia Fitts, the daughter of a local reverend, and as tradition holds, he bought the home to impress her. Sadly, this attempt would go horribly awry.

Joseph Parkes Jr who moved Centennial to Williamson County

“That old fool wanted me to leave my nice, comfortable house and move out to that monstrosity!”

After preparing a stone foundation atop a hill on his property, Joseph had the pavilion dismantled and the pieces numbered to simplify the reassembly. Wagons, each drawn by four mules, transported the parts about twenty-five miles on Hillsboro Road to the new site in Williamson County. The process took several trips, and incredibly, not a single window was broken, nor was the marble porch floor chipped. The structure was pieced back together with the utmost care and thought. Joseph even hired the original workman to replaster the walls. To make the building more livable, a few changes were made, such as additional windows and larger wings on both sides of the dome-capped central section.

As the story goes, Joseph brought his beloved Sophia to the home while it was under construction and proposed marriage. However, she was less than impressed with the house and rejected his offer. Sophia was quoted as later saying, “That old fool wanted me to leave my nice, comfortable house and move out to that monstrosity!” Both remained unmarried for the remainder of their lives, but continued to see each other. Joseph halted work on the unique house for several years, opting instead to live in his parent’s residence on Columbia Avenue where Carter’s Court is now located. He was often seen walking to Sophia’s home, which still stands at 604 West Main Street. Joseph never moved into his house on the hill. However, he did keep up his dairy farm on the surrounding acreage.

After Joseph’s ownership, the property passed through several hands. In 1924, it was purchased by Walter and Ida Carlisle. They named the home “Centennial Hall” and continued to operate the dairy farm. Their son Walter, Jr. later lived in the house with his wife, Derry, and their three children, who enjoyed roller skating around the dome room. Derry was a longtime editor for Franklin’s former newspaper, The Review-Appeal.

In 1984, Vanderbilt professor Dr. Tomlinson Fort, Jr. acquired Centennial Hall and undertook a meticulous renovation and restoration. A rear addition was constructed as well. He married artist Nancy Blackwelder under the dome.

The current owners, Dr. John and Elizabeth Spooner, bought the house from the Forts in 2012. Nine years later, they began work on an expansion of the home’s north side, adding several bedrooms, bathrooms, a laundry room and a recreation room. Though the addition has all the comforts of a modern space, it has a decidedly historic feel. The Spooners salvaged many materials from other structures, such as light fixtures from an old hotel in Chicago and windows from the Holt house that once stood on Columbia Avenue. High ceilings and thick trim create a seamless transition from the original part of the home, as do the floors, which were sourced from a North Carolina business that slow-grows pine trees. This process produces wood with a tight grain that matches Centennial Hall’s original, heart-pine floors. To add to the aged look, the planks were installed with intentional gaps.

In addition to making the home more livable for their family, the Spooners have devoted much effort to maintaining the original structure. The dome, which stretches above their dining room, is remarkably well-preserved. Even the pulley system still functions, opening four glass windows at the base of the dome. Several other nods to the home’s past can be found throughout this portion of the residence, such as a gallery of photos documenting the house over the years and a bed thought to have been used by the Pythians during the 1897 exposition.

Centennial Hall has dodged demolition, survived relocation and withstood the test of time. After nearly 130 years, its walls remain sturdy keepers of countless stories. Now, with the Spooners as stewards, the future seems limitless for this old house. Though its earliest chapters were a bit tumultuous, Centennial Hall has found a happy resting place atop its hill in Williamson County.